Principles and Practices of Transaction Recovery in Distributed Databases

This article is based on a presentation from OceanBaseDev Meetup #1 in Shanghai. The meetup focused on distributed transactions and their practical implementation in distributed databases. The video recording and slides from the presentation are available at the end of this article.

About the author: Kong Fanyu (Jingyan), a technical expert at Ant Group, joined the OceanBase Database transaction team in 2016 and contributed to the design and development of OceanBase Database V1.0 and V2.0. He currently focuses on data compaction and crash recovery in OceanBase Database.

Transaction recovery has been an essential aspect of relational databases since their emergence in the 1970s. Distributed databases present new challenges for transaction recovery. This article discusses the specific challenges of transaction recovery in both standalone and distributed databases, explores typical solutions to these challenges, and provides practices of transaction recovery in OceanBase Database.

Standalone Databases

Database transactions are characterized by the following four properties: atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability (ACID). Among these properties, atomicity and durability are related to transaction recovery.

-

Atomicity ensures that either all or none of the modifications made by a transaction are applied.

-

Durability ensures that the results of committed transactions are not lost in the event of database crashes.

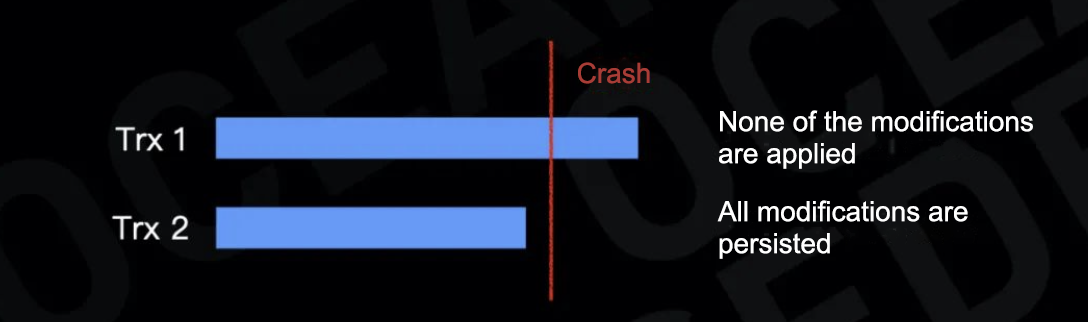

The following figure demonstrates the execution of two transactions.

Consider a scenario where the database crashes: Trx1 is not completed while Trx2 is committed. Atomicity and durability require that, upon crash recovery, none of the modifications made by Trx1 be applied and all of the modifications made by Trx2 be persisted. To achieve this, the database must perform two actions after it restarts:

-

Rollback: Undo the modifications made by all uncompleted and rolled back transactions.

-

Redo: Reapply the modifications made by all committed transactions to ensure durability.

Shadow Paging

Shadow paging is a simple approach to ensuring transaction atomicity and durability. This approach is easy to understand. The database maintains two separate data versions: a master version and a shadow version. All modifications made by a write transaction are written to the shadow version. Read transactions operate on the master version. The shadow version is invisible to read transactions. When a write transaction commits, the shadow version is atomically switched to become the new master version.

When the database restarts upon a crash, it simply cleans up any residual shadow version data, without the need to roll back or redo transactions.

Lightning Memory-Mapped Database (LMDB) exemplifies the shadow paging approach. As a memory-mapped key-value database, LMDB employs a copy-on-write approach to update its B+ tree index schema upon transaction modifications. During a write transaction, LMDB modifies a copy of the affected B+ tree pages and generates a new root node. Before the transaction commits, LMDB persists the new root node to the disk. When a read transaction reads data, it always starts from the latest root node that has taken effect.

Data Persistence Strategies

As mentioned earlier, when a database restarts upon a crash, it must perform rollback and redo operations. The purpose of rollback is to reverse modifications from uncommitted transactions on disks. As shadow paging does not modify the master version before a transaction commits, rollback is not needed. The purpose of redo is to reapply non-persisted modifications from committed transactions. As shadow paging persists all modifications to disks and modifies the master version before a transaction commits, redo is also not needed.

Therefore, the necessary transaction recovery operations depend on the data persistence strategy used during transaction execution.

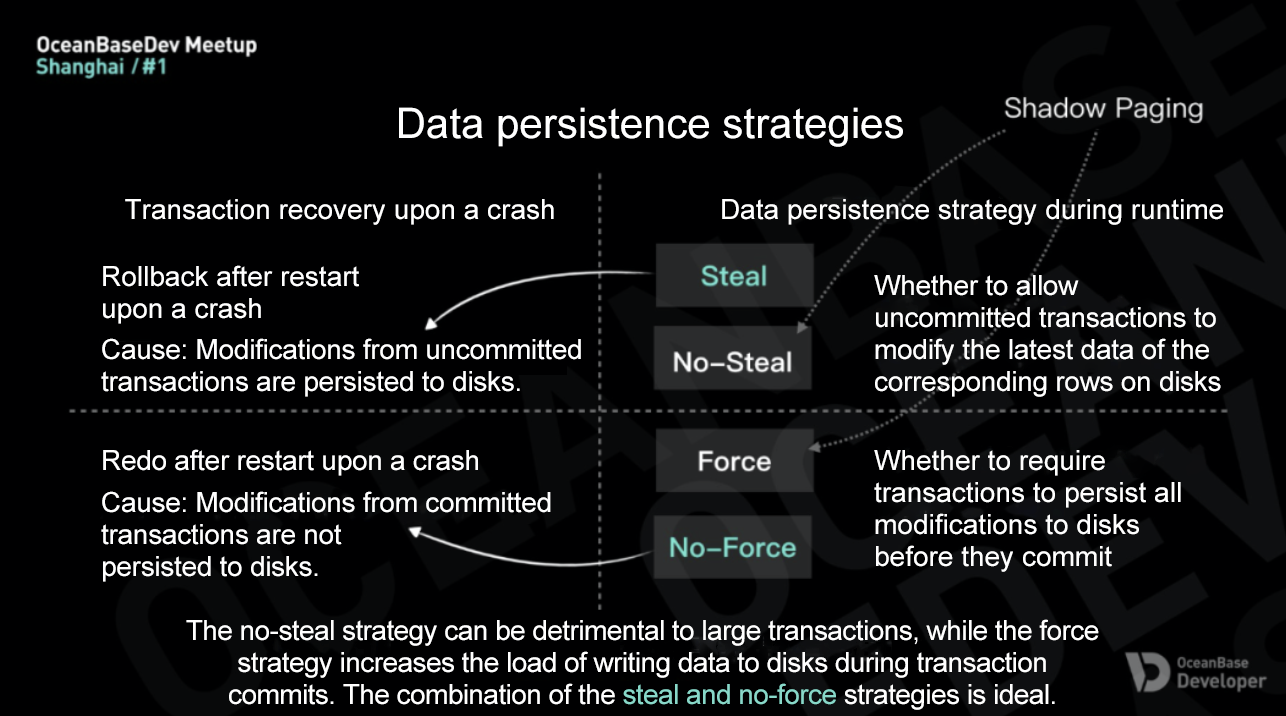

Databases employ two data persistence strategies during transaction execution:

-

Steal or no-steal: Determine whether to allow uncommitted transactions to modify the latest data on disks during transaction execution.

-

Force or no-force: Determine whether to require transactions to persist all modifications to disks before they commit.

Database systems that implement the steal strategy require a rollback mechanism to reverse modifications from uncommitted transactions after restart upon a crash. Database systems that implement the no-force strategy require a redo mechanism to reapply non-persisted modifications from committed transactions after restart upon a crash.

Database systems using shadow paging implement both no-steal and force strategies, resulting in a simplified crash recovery process. However, this simplicity comes at the cost of runtime performance. The no-steal strategy can be detrimental to large transactions because it does not allow transactions to persist modifications to disks before transaction commits. The force strategy increases the load and latency of writing data to disks during transaction commits. Generally, the combination of the steal and no-force strategies is ideal for database systems that prioritize runtime performance.

Logging

So how do we implement the steal and no-force strategies in a database system? Let's now explore several log-based implementation methods.

Redo Logging

If redo logs are generated to record the new values after transaction modifications, the system can replay the redo logs to redo committed transactions when it restarts upon a crash. However, the system cannot roll back uncommitted transactions. Therefore, systems that use redo logging must comply with the following rules:

-

Generate a redo log that records the new value for every modification.

-

Implement the no-steal strategy to prevent transactions from persisting modifications to disks before transactions commit or before commit logs are persisted to disks.

-

Implement the no-force strategy to require transactions to persist all their logs rather than data to disks before transaction commits.

RocksDB, when WriteUnprepared is not considered, serves as a typical example of a database that uses redo logs. Transaction modifications are not directly persisted to disks before transaction commits but are instead buffered in a memory-resident, transaction-specific WriteBatch. Upon a transaction commit, RocksDB generates redo logs for all modifications, persists the logs to disks, and then writes the data within the WriteBatch to the MemTable.

Database systems using redo logging implement both the no-steal and no-force strategies. As mentioned earlier, the no-steal strategy can be detrimental to large transactions.

Undo/Redo Logging

If you also generate undo logs, although not necessarily implemented as logs, to record the old values before transaction modifications, the system gains the ability to roll back uncommitted transactions when it restarts upon a crash. This approach is called undo/redo logging. It complies with the following rules:

-

Generate logs that record both the old and new values for every modification.

-

Implement the steal strategy to allow uncommitted transactions to persist modifications to disks after the corresponding logs are persisted to disks.

-

Implement the no-force strategy to require transactions to persist all their logs rather than data to disks before transaction commits.

The renowned Oracle database uses this pattern. Oracle generates corresponding undo and redo records for every transaction modification. Undo records are stored in undo blocks. Before writing modified (dirty) pages to disks, Oracle ensures that the corresponding transaction logs for the dirty pages are persisted to disks. Before committing a transaction, Oracle persists all the logs of the transaction to disks.

Database systems using undo/redo logging implement both the steal and no-force strategies. This design is prevalent in most popular relational database systems, such as Oracle, MySQL, and PostgreSQL.

Log Recycling

All log-based systems face the challenge of log recycling. Although retaining all logs ensures transaction recovery, unbounded log growth is unsustainable. Moreover, recovering a database from the very first log upon a crash results in an unacceptable recovery speed. Therefore, checkpointing is essential to minimize the number of logs required for crash recovery.

The simplest checkpointing method involves the following steps:

-

Suspend transaction processing by halting the initiation of new transactions and waiting for existing transactions to complete.

-

Persist all non-persisted modifications in memory to disks.

-

Mark the current point in time as a valid checkpoint.

-

Resume transaction processing.

The correctness of this method is readily apparent: After Step 2, complete data resides on disks, thus eliminating the need for logs. However, this method has an obvious drawback. It requires complete suspension of transaction processing, which is unacceptable in most cases.

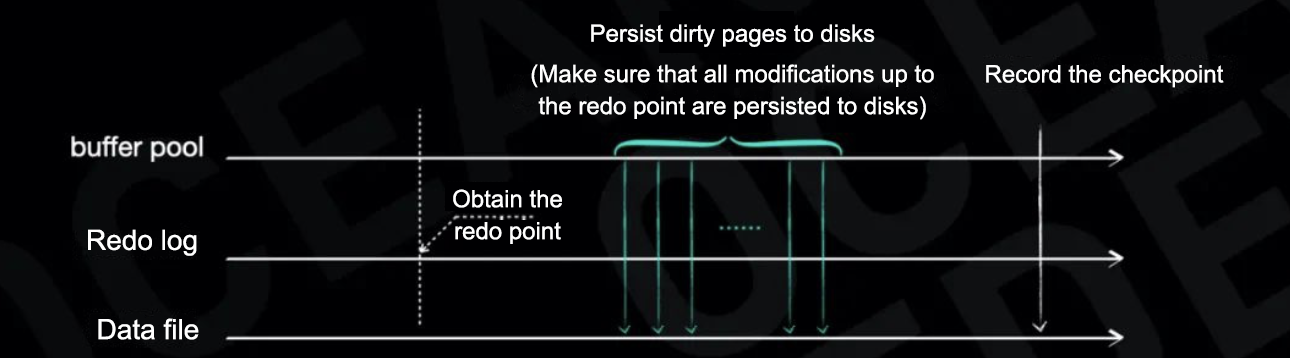

Many other checkpointing methods can mitigate this issue. Consider the media recovery checkpoint in Oracle as an example. It involves the following steps:

- Obtain the current system change number (SCN), which serves as the redo point.

- Notify the Database Writer (DBWR) process to persist all dirty pages to disks.

- Record the SCN as the latest checkpoint in the metadata.

This process does not interrupt ongoing transactions. Its correctness stems from the guarantee that, once dirty page flushing is complete, all modifications up to the redo point are persisted to disks, eliminating the need for log replay during crash recovery.

Challenges Posed by Distributed Databases

In distributed databases, transaction recovery aims to ensure transaction atomicity and durability. Unlike standalone databases, distributed databases have data modifications spread across different nodes.

In the preceding example, the transaction modifies data on three nodes. To commit the transaction, the system must ensure that all modifications to the data on the three nodes are committed at the same time. Partial commits or rollbacks are unacceptable.

Saga

Introduced in 1987, the Saga pattern is an approach to break down long-lived transactions while ensuring their overall atomicity. You can also use Saga to resolve issues with distributed transactions. The core idea of Saga is to generate a compensating transaction for each subtransaction. During the commit of a distributed transaction, subtransactions are committed sequentially on involved nodes. If a failure occurs, compensating transactions are executed for the committed subtransactions on the nodes to roll back the committed modifications.

In the preceding example, a distributed transaction generates a subtransaction on each of three nodes. During the commit of the distributed transaction, the subtransactions on the first two nodes are committed, but the subtransaction on the third node fails to be committed. In this case, compensating transactions must be executed for the two successfully committed subtransactions to roll back the modifications made by them.

This approach simplifies the normal commit process but adds complexity to rollback through compensation.

2PC

Two-phase commit (2PC) is probably the most renowned solution for achieving atomicity in distributed transactions. As its name suggests, 2PC divides the transaction commit process into two phases:

-

Prepare: The coordinator notifies participants to prepare. Upon receiving the prepare request, participants write a prepare log entry respond to the coordinator with the message "Prepare OK."

-

Commit: Upon receiving "Prepare OK" from all participants, the coordinator notifies participants to commit the transaction.

Every node must record the result of each phase in persistent logs for state recovery.

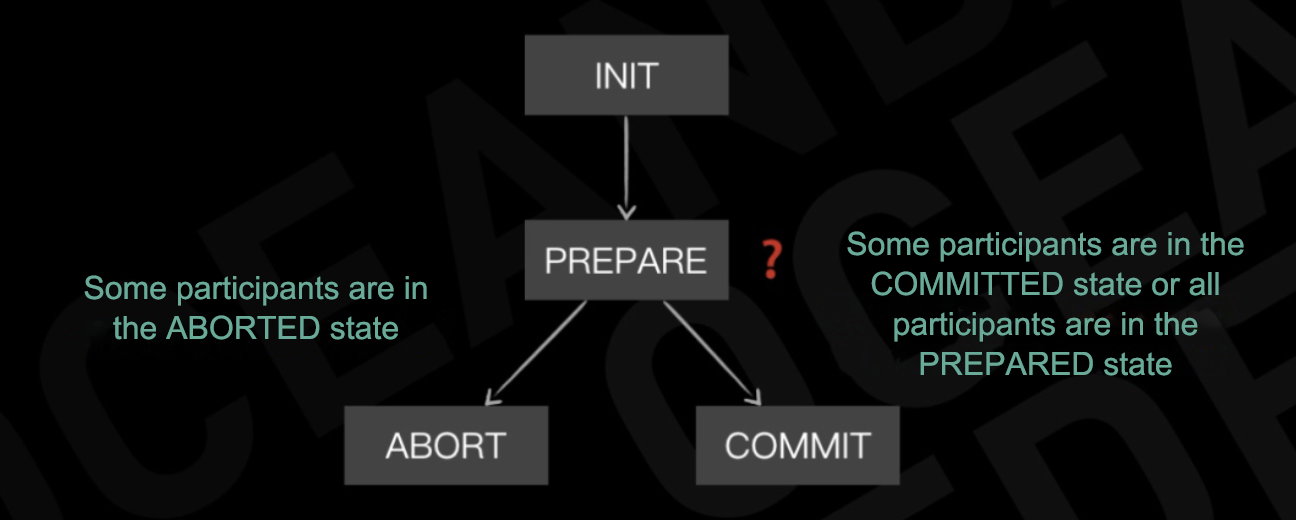

While the 2PC protocol itself is straightforward, its core lies in how it handles crashes. If a participant crashes before sending "Prepare OK" to the coordinator, the coordinator assumes that the participant decides to roll back the transaction. If the coordinator crashes, participants decide their next actions based on their states.

The preceding figure shows the state machine of participants in 2PC. If participants have responded with "Prepare OK" and are prepared, they must wait for the notification from the coordinator to decide the final transaction state. We refer to this as the participants being in the "in-doubt" state. If the coordinator crashes at this point in time, the 2PC process gets blocked. This is a challenge that all systems using the 2PC protocol must address.

Many systems employ the 2PC protocol. Consider Postgres-XC as an example. Postgres-XC stores data across different data nodes. When committing a distributed transaction, the coordinator uses the 2PC protocol to ensure the atomicity of the transactions that modify data across these data nodes.

The Percolator protocol, which is popular in recent years, is a variant of the 2PC protocol. It provides a comprehensive solution for handling distributed transactions. This article focuses on how Percolator ensures transaction atomicity. Developed by Google, Percolator combines single-row transactions into multi-row transactions on top of Bigtable, which supports only low-level transactions.

When committing a multi-row transaction, Percolator performs the following steps:

- Select a row as the primary record and write it to Bigtable. The primary record stores the overall transaction state, which is initially marked as "uncommitted."

- Write other rows as secondary records to Bigtable. Secondary records reference the location of the primary record and determine their state by querying the transaction state in the primary record.

- Update the transaction state in the primary record to "committed."

- Asynchronously remove the transaction states from the secondary records.

In the 2PC context, every secondary record in Percolator acts as a participant in the entire distributed transaction while the primary record acts as the coordinator. After all participants have persisted their data, updating the transaction state in the primary record is equivalent to the coordinator writing a commit log.

Transaction Recovery in OceanBase Database

OceanBase Database employs a share-nothing architecture, where data is distributed across nodes based on sharding rules. Every node has its own storage engine and manages distinct data partitions. Paxos log replication ensures high availability for each partition. Transactions operating on a single shard are executed as local transactions. Transactions spanning multiple shards are distributed transactions that face atomicity challenges.

Local Transaction Recovery

OceanBase Database uses multiversion concurrency control (MVCC) to manage transaction concurrency, maintaining multiple data versions for each transaction modification. Built on a log-structured merge-tree (LSM-tree), the storage engine on each shard periodically compacts data.

As shown in the following figure, OceanBase Database writes modifications as new data versions to the currently active in-memory MemTable. When the MemTable uses a predefined amount of memory, OceanBase Database freezes it and creates a new active MemTable. Then, OceanBase Database compacts the frozen MemTable into SSTables on disks. When receiving a read request, OceanBase Database merges multiple versions from all SSTables and the active MemTable into the required data version.

OceanBase Database employs undo/redo logging for local transaction recovery. During a write transaction, OceanBase Database generates redo logs and uses data of the old version maintained by MVCC as undo information, implementing both the steal and no-force strategies for data persistence. During crash recovery, OceanBase Database uses redo logs to replay committed but not yet persisted transactions, and uses the retained data of the old version to roll back persisted modifications from uncommitted transactions.

Distributed Transaction Recovery

For transactions spanning multiple shards, OceanBase Database uses 2PC to ensure atomicity.

As shown in the preceding figure, when a distributed transaction commits, OceanBase Database selects one shard as the coordinator to execute the 2PC protocol across all shards. As previously discussed, coordinator crashes can pose a challenge. In OceanBase Database, all shards replicate logs through Paxos for multi-replica high availability. When the leader crashes, a follower from the same shard is promoted to become the new leader. This way, OceanBase Database prevents the coordinator crash issue by ensuring high availability for both the participants and the coordinator based on the majority rule.

With high availability of participants ensured, OceanBase Database optimizes the coordinator to be stateless. In standard 2PC, the coordinator persists its state by logging. Otherwise, if the coordinator and participants crash simultaneously, the transaction state may become inconsistent after the coordinator recovers. However, if we assume that participants never crash, the coordinator does not need to write logs to record its state.

The preceding figure shows the state machine of the coordinator in 2PC. If the coordinator does not write logs, it cannot decide whether its previous state is ABORTED or COMMITTED after a switchover or crash recovery. In this case, the coordinator can restore its state by querying the participants. As participants are highly available, the coordinator can always restore the state of the entire transaction.

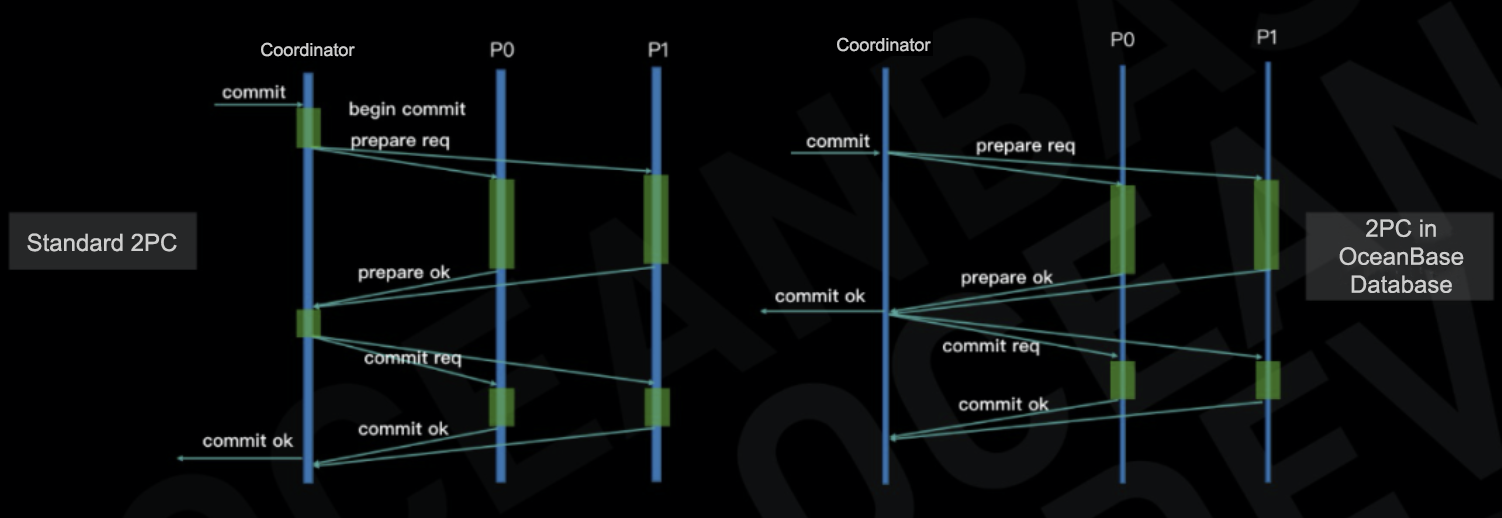

OceanBase Database also optimizes the 2PC protocol for lower latency. In the standard 2PC protocol, a response is sent to the client after the commit phase ends. In OceanBase Database, a response is sent to the client after the prepare phase ends.

In the preceding figure, green sections represent log writes. In the standard 2PC protocol on the left, the commit latency that users perceive is the time spent on four log writes and two remote procedure call (RPC) round trips. In the 2PC implementation in OceanBase Database on the right, as the coordinator no longer writes logs and OceanBase Database responds to the client earlier, the commit latency that users perceive is the time spent on one log write and one RPC round trip.

Afterword

Relational databases have a long and rich history, yet the field remains vibrant and dynamic. Over the years, hardware advancements have spurred new technologies and ideas. The transaction recovery solutions for standalone and distributed databases that we have discussed in this article demonstrate how database technology has evolved to keep pace with hardware advancements. What does the future hold? With larger memory capacities, faster networks, cheaper disks, and even the widespread use of non-volatile memory, the possibilities for database technology are vast. We are excited to see what the future brings. If you are interested, join the OceanBase team to shape the future of database technology with us.

References

To share your feedback, visit http://oceanbasedev.mikecrm.com/w77l9yx.

To watch the video, visit https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1Rk4y1k7Vf.

To view the PowerPoint file, visit https://tech.antfin.com/community/activities/1283/review/1011.

Follow us in the OceanBase community. We aspire to regularly contribute technical information so we can all move forward together.

Search 🔍 DingTalk group 33254054 or scan the QR code below to join the OceanBase technical Q&A group. You can find answers to all your technical questions there.