Evolution of Database Query Engines

In relational databases, the query scheduler and plan executor are as crucial as the query optimizer, and their importance is increasing with advancements in computer hardware. In this article, Yuming, a technical expert from the OceanBase team who was born in the 1990s, will walk you through the milestones in the evolution of plan executors.

About the author: Wei Yuchen, a technical expert from the OceanBase team of Ant Group, has been working on SQL parsing, execution, and optimization since joining the OceanBase team in 2013.

When we talk about SQL queries in relational databases, the query optimizer naturally comes to mind. It is undoubtedly a crucial and complex module in relational computations, responsible for determining the most efficient execution plan to achieve optimal query results. However, two equally important modules contribute to relational computations: the query scheduler and the plan executor.

In the early stages of relational database development, I/O limitations overshadowed computation time for queries, diminishing the roles of the query scheduler and plan executor. Query performance primarily hinged on the execution plan selected by the query optimizer. Nowadays, with advancements in computer hardware, the query scheduler and plan executor are gaining significant prominence. This article focuses on some milestones in the evolution of plan executors.

Classical Volcano Model

The Volcano model is a classical row-based streaming iterator model used by well-known mainstream relational databases such as Oracle, SQL Server, and MySQL.

In the Volcano model, all algebraic operators act as iterators, each providing a set of simple interfaces: open(), next(), and close(). A query plan tree consists of these relational operators, which return a row upon each call to next(). Each operator has its own flow control logic for next(). Data is passively pulled through a chain of nested next() calls from the top to the bottom of the plan tree.

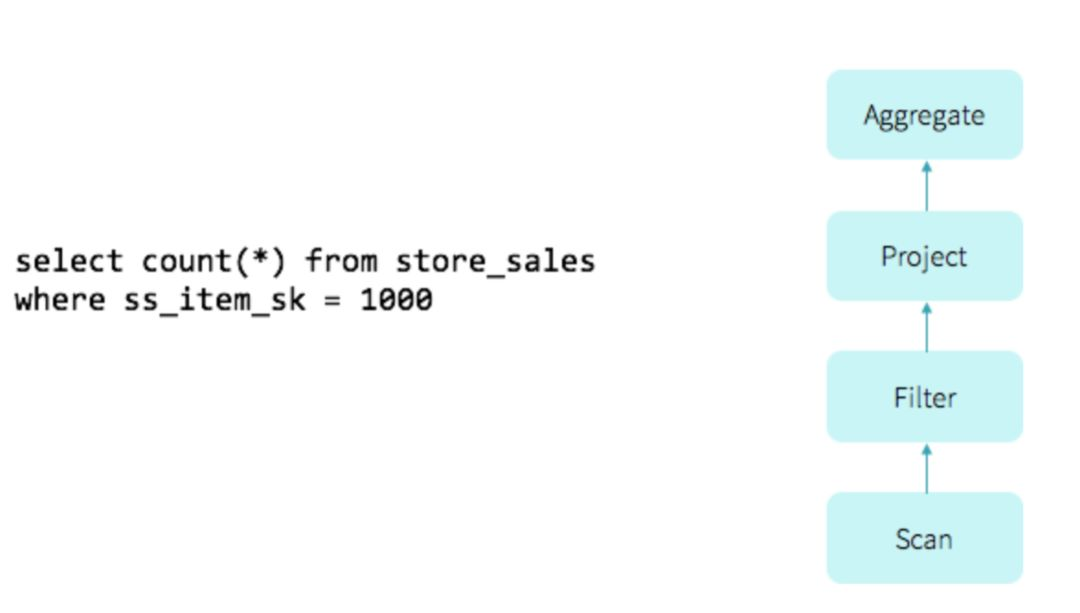

The preceding figure shows the query iterator model used in Spark 1.0, a model also used in OceanBase V0.5. This model is a simple example of the Volcano model. The control flow for pulling data originates at the topmost AGGREGATE operator and proceeds down to the bottom of the execution tree. Data, on the other hand, flows upward from the bottom of the execution tree.

In the Volcano model, each operator treats its input from the lower-level operator as a table, with each call to next() retrieving one row of data. This design offers the following benefits:

- Each operator performs independent algebraic computations and can be placed anywhere in the query plan tree as the query relationship changes. This simplifies operator algorithm implementation and enhances extensibility.

- Data flows between operators in a row-oriented manner. As long as flow-disrupting operations such as SORT are absent, each operator can operate efficiently with minimal buffering, reducing memory consumption.

However, the nested operator model has its drawbacks:

- Flow control in the Volcano model is a passive pull-based process. Every row of data flowing through each operator incurs additional flow control operations. This results in many redundant flow control instructions when data flows between operators.

- The next() calls between operators lead to deeply nested virtual function calls, preventing the compiler from inlining virtual functions. Each virtual function call requires a virtual function table lookup, increasing branch instructions. The complex nesting of virtual functions hinders CPU branch prediction, often causing prediction failures that disrupt the CPU pipeline. All these factors contribute to CPU execution inefficiency.

Generally, the direct overhead of a query depends primarily on two factors: the data transfer overhead between storage and operators, and the time spent on data computation.

The Volcano model was first introduced by Goetz Graefe in 1990 in his paper Volcano—An Extensible and Parallel Query Evaluation System. In the early 1990s, memory was expensive, and I/O was a significant bottleneck compared to CPU execution efficiency. This I/O bottleneck, the so-called "I/O wall" problem, between operators and storage was the primary limiting factor for query efficiency. The Volcano model allocated more memory resources to I/O caching than to CPU execution efficiency, which was a natural trade-off given the hardware constraints at the time.

As hardware advances brought larger memory capacities, more data can be stored in memory. However, the relatively stagnant performance of single-core CPUs became a bottleneck. This spurred numerous optimizations aimed at improving CPU execution efficiency.

The simplest and most effective way to integrate and optimize the execution efficiency of operators is to reduce the function calls of operators during the execution process. The Project and Filter operators are the most common operators in plan trees. In OceanBase V1.0, we fuse these operators into other specific algebraic operators. This significantly reduces the number of operators in a plan tree and minimizes the number of nested next() calls between operators. Integrating the Project and Filter operators as internal capabilities of each operator also enhances code locality and CPU branch prediction.

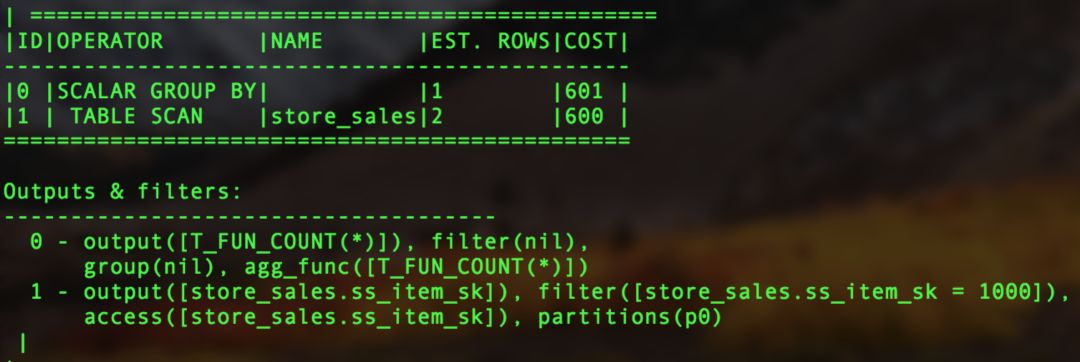

The preceding figure shows the execution plan of the query select count(\*) from store\_sales where ss\_item\_sk=1000; in OceanBase V1.0. The number of operators decreases from four to two, with the Filter and Select operators fused as local operations into the other operators.

RowSet Iteration

The Volcano model can be further optimized by using a RowSet mechanism. Instead of processing data row by row, the RowSet mechanism operates on batches of rows. This keeps computation localized within next() without frequently switching between function calls, thus ensuring code locality and reducing the number of function calls.

By transforming the data flow in each step into localized loops, the RowSet mechanism leverages modern compiler technology and CPU dynamic branch prediction technology to optimize simple loop instructions to the fullest extent. Furthermore, RowSet construction can be accelerated by using single instruction multiple data (SIMD) instructions of CPUs, which is more efficient than per-row copies in memory. This significantly boosts the execution efficiency of queries that produce large result sets.

Push Model

The push model was initially used in stream computing. With the advent of the big data era, it has been widely adopted in memory-based online analytical processing (OLAP) databases such as HyPer and LegoBase.

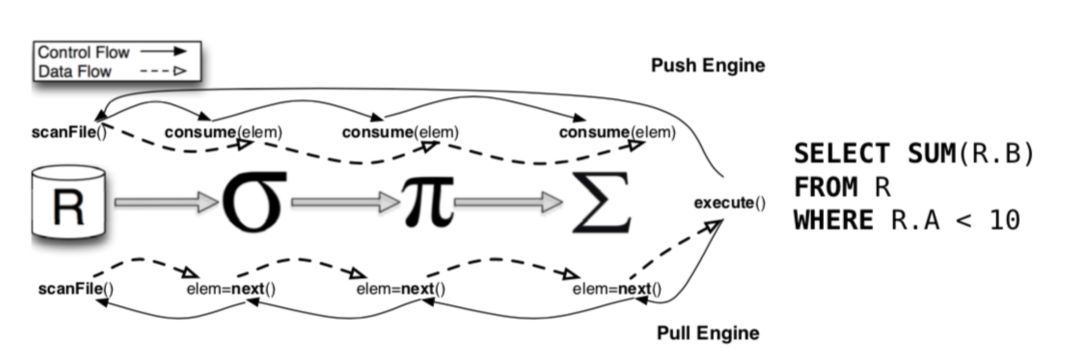

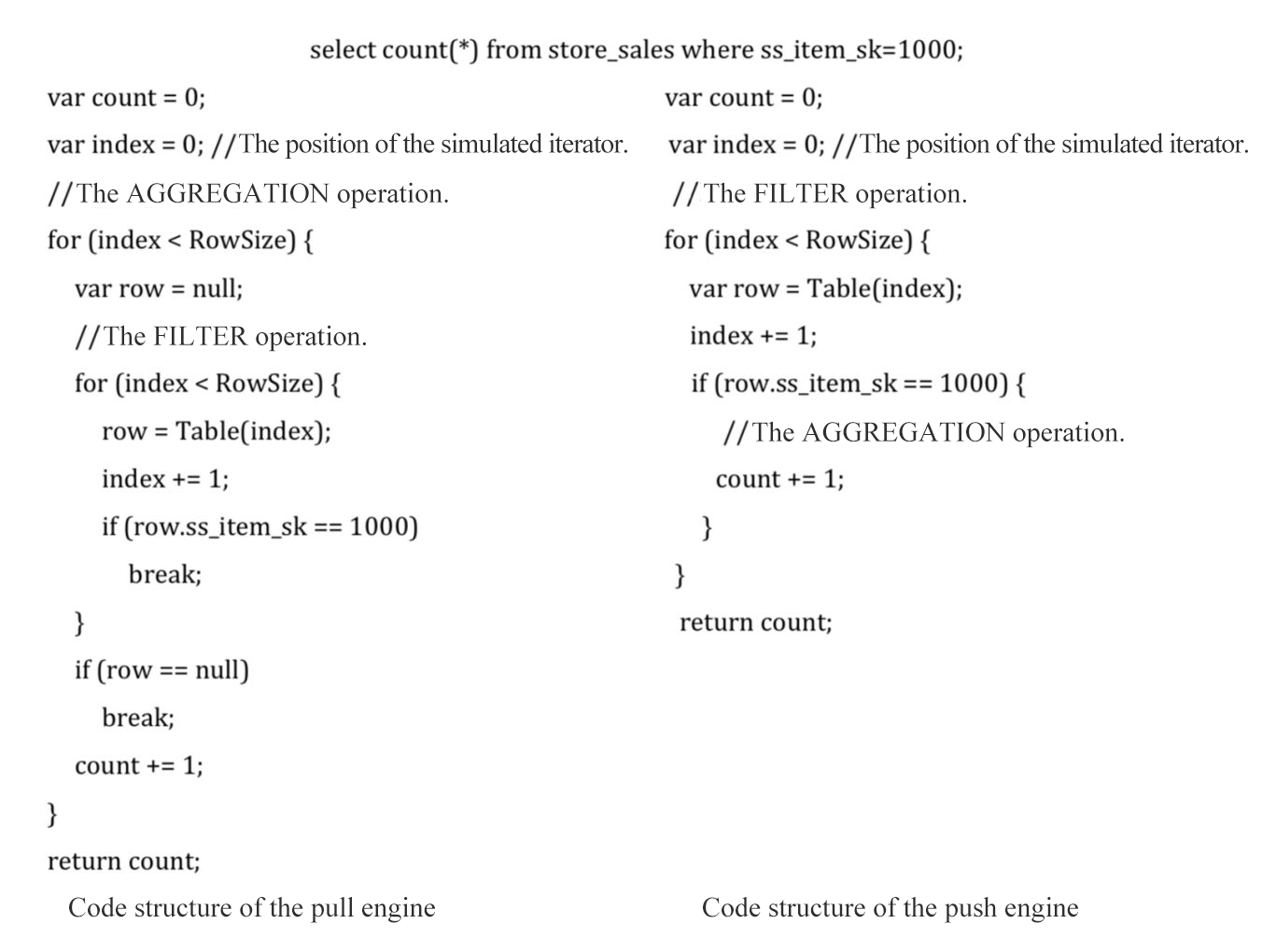

The preceding figure shows the different control and data flow directions of the pull and push models. As shown, the control flow of the pull model aligns more intuitively with our understanding of query execution. In this model, higher-level operators request and process data from lower-level operators on demand, which is essentially a series of nested function calls. Conversely, the push engine pushes computations from higher-level operators down to the operators that produce the data. Data producers then drive the consumption of this data by the higher-level operators.

To better compare the impact of the pull and push models on code structure, we illustrate the implementation of the next() interface of each operator in the aforementioned query in pseudocode, as shown in the following figure.

As shown in the preceding figure, the push model transforms the nested call structure of data iteration compared to the pull model. This simplifies the instruction switching process during query execution, ensuring improved code locality and higher CPU execution efficiency. However, the push model is more complex to implement. The HyPer system implements its computation and push engine by using the visitor design pattern. The basic idea is that each operator provides two interfaces: produce() for data production and consume() for data consumption. Different from next() in the pull model, consume() focuses solely on the relational algebra logic of the operator while produce() manages the flow control logic.

One challenge is that operators whose relational algebra operations are inherently tied to flow control, such as LIMIT, MERGE JOIN, and NESTED LOOP JOIN, are difficult to implement by using the push model. Their execution efficiency within the push model may be inferior to that within the pull model. The HyPer paper does not offer a solution to this, presumably because HyPer focuses on OLAP scenarios, where flow control operators are less common, making their execution efficiency less of a concern. In extreme cases, these operations can be handled as special cases within other operators.

Integration of Pull and Push Models

For a general-purpose relational database, it is necessary to consider the drawbacks of the push model. In online transaction processing (OLTP) scenarios, operations such as MERGE JOIN and NESTED LOOP JOIN are far more common than HASH JOIN. Therefore, it is a wise choice to integrate the pull and push models in the execution engine of the general-purpose relational database. In some time-consuming materialization operations, such as building a hash table for a hash join or performing aggregation, a callback function can be passed down to the lower-level operator through the next() interface. This offloads the time-consuming blocking computation to the next blocking operator through the callback. When the lower-level operator produces all data, it invokes callback functions in the callback list in sequence.

Callbacks are not used to push down operations such as LIMIT, MERGE JOIN, and NESTED LOOP JOIN. This implementation requires only minimal changes to the original Volcano model while still realizing some of the advantages of the push model. This represents a reasonable trade-off.

Compiled Execution

While the pull and push models influence the code layout of the execution process, interpreted execution inherently involves virtual function calls between operators. With advances in computer hardware, memory capacities have grown significantly, allowing more data to be cached in memory and thereby reducing disk access frequency. This mitigates the "I/O wall" effect. However, the inability to leverage CPU registers during interpreted execution leads to frequent memory access, creating a "memory wall" between the CPU and memory. To resolve this issue, an increasing number of in-memory databases, such as HyPer, MemSQL, Hekaton, Impala, and Spark Tungsten, adopt compiled execution to optimize query efficiency.

Compared to interpreted execution, compiled execution offers the following benefits:

1. Inlining of virtual function calls: In the Volcano model, processing one row of data requires at least one call to next(). These function calls are implemented by the compiler through virtual function dispatches (vtable lookups). Compiled execution, however, eliminates these function calls altogether and optimizes away many control flow instructions required by interpreted execution. This makes CPU execution more efficient.

2. Intermediate data in memory vs CPU registers: In the Volcano model, operators pass row data by storing it in a memory buffer, necessitating at least one memory access per execution. Compiled execution, however, eliminates such data iteration and stores intermediate data directly in CPU registers provided that sufficient CPU registers are available. Register access is significantly faster than memory access, typically by an order of magnitude.

3. Loop unrolling and SIMD: When running simple loops, modern compilers and CPUs are incredibly efficient. Compilers automatically unroll simple loops and generate SIMD instructions in each CPU instruction to process multiple tuples. CPU features such as pipelining, prefetching, and instruction reordering enhance the execution efficiency of simple loops. However, compilers and CPUs offer limited optimization for complex function calls, while the Volcano model has highly intricate flow control calls.

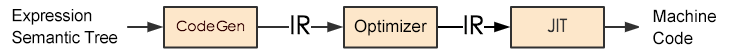

In OceanBase V2.0, we use the low-level virtual machine (LLVM) framework to optimize compiled execution for expression operations and Procedural Language (PL) code in the execution engine. Here we introduce the compiled execution of expressions in OceanBase.

The compilation phase involves three main steps:

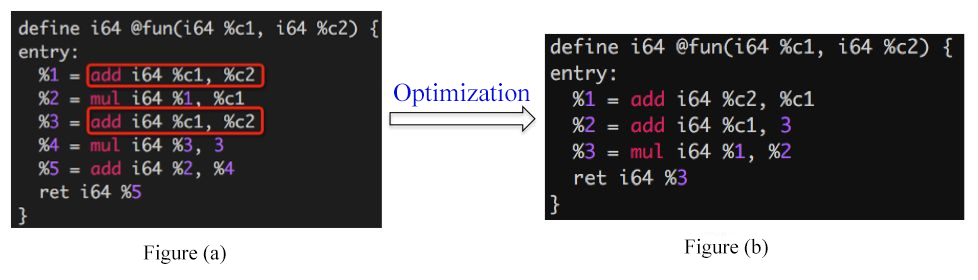

1. Intermediate representation (IR) code generation: Consider the expression (c1+c2)*c1+(c1+c2)*3, where all operands are of the BIGINT type. By analyzing the semantic tree of the expression, the LLVM CodeGen API generates IR code, as shown in Figure (a).

2. Code optimization: In the original code, the expression c1+c2 is computed twice. LLVM extracts it as a common subexpression. As shown in Figure (b), the optimized IR code computes c1+c2 only once, and the total number of executed instructions also decreases. If you use interpreted execution for expressions, all intermediate results are materialized in memory. Compiled code, however, allows you to store intermediate results in CPU registers for direct use in the next computation, boosting execution efficiency. LLVM also offers many similar optimizations, which we can use directly to speed up expression computation.

3. Just-in-time (JIT) compilation: On-Request Compilation (ORC) JIT in LLVM compiles optimized IR code into executable machine code and returns a pointer to the compiled function.

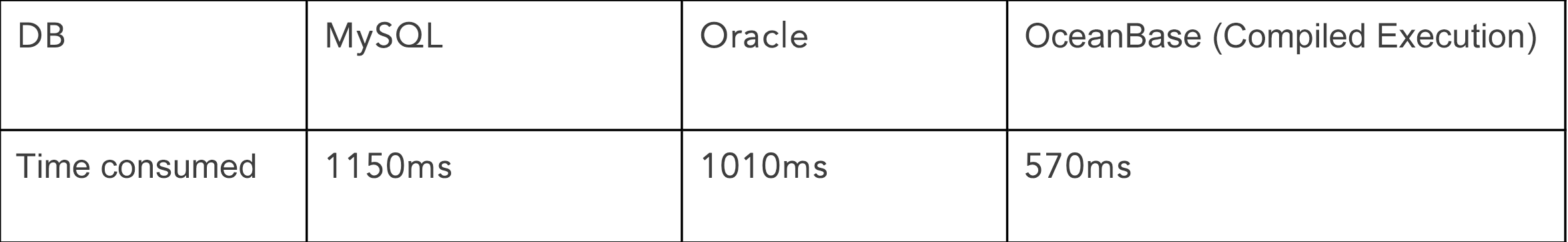

Results Comparison

We compared the performance of several databases in the same test environment by executing the following SQL statement on a 1-GB TPC-H lineitem table that has approximately 6 million rows of data:

SELECT SUM(CASE WHEN l_partkey IN(1,2,3,7)

THEN l_linenumber + l_partkey +10

ELSE l_linenumber + l_partkey +5

END) AS result

FROM lineitem;

As shown in the preceding figure, compiled execution offers a significant performance advantage over interpreted execution when dealing with large data volumes. This advantage increases proportionally with the data size. However, compiled execution has its drawbacks:

-

Directly compiling the Volcano model into code blocks may lead to exponential code growth due to function inlining, hindering execution efficiency improvements. Therefore, compiled execution benefits from integrating pull and push models, rather than relying solely on the pull model. If you are interested in compiled execution, we recommend that you read Efficiently Compiling Efficient Query Plans for Modern Hardware by Thomas Neumann, the author of HyPer. This paper details optimization techniques for complex operators and provides coding strategies to maximize the efficiency of compiled execution.

-

Generating binary code for compiled execution is time-consuming, often taking 10 ms or more. For OLAP databases, this compilation time is acceptable because data computation dominates query time. However, for OLTP databases, this compilation time is intolerable for frequent, small queries. To address this issue, OceanBase stores and reuses compilation results in the plan cache, eliminating recompilation of identical queries.

Afterword

Software technology development goes hand-in-hand with hardware advancements. Aligning the software technology stack with hardware advancements brings significant benefits to system designs. While OceanBase is not strictly an in-memory database, effective partitioning allows us to cache frequently accessed data in memory, enabling OceanBase to function like a distributed in-memory database. Therefore, the optimization principles for in-memory databases also apply to the architecture of OceanBase.

OceanBase is turning these academic ideas into engineering practices, such as wider adoption of compiled execution, computation pushdown, and distributed parallel execution. We are also assessing how columnar storage formats influence database execution engine technology and exploring methods to integrate the advantages of columnar storage engines into OceanBase. This will enhance the execution capability of OceanBase in analytical computing scenarios, solidifying its role as a hybrid transactional/analytical processing (HTAP) database.